Lobster Fishing from Fortune

The Crew of Johnston’s Factory, 1908.

As with much of the Island, the prosperity of the people of Fortune has long been intertwined with the river which gives the community its name, and as a result the local people have sought to make their living from the waters of Fortune just as much as they have done so on the land. The calm and winding waters of Fortune River make their way silently towards Bay Fortune and on into the Atlantic, and it is this soft mingling of fresh and salt water, coupled with the tides, that has fostered a breeding ground for some of the finest lobsters on the Island, which in turn has led to the lobster fishery becoming an economic staple of the area. The livelihoods of generations have stemmed from the water’s ability to provide for those who fish it, a proud tradition which continues to this day. But unlike today’s modern lobster industry, with its large and technologically advanced boats and equipment, things weren’t always so easy, and, as you will discover, lobster was much more than a job, it was a way of life.

Developing the Harbour

Records indicate that a breakwater was first established in Fortune somewhere around the year 1900, on the north side of the harbour. As was the case in many of our small harbours, the establishment of a breakwater was necessary in order to facilitate any sort of fishing industry, for the breakwater was required to keep the wrath of the sea at bay. It was lamented at the time that the provincial government was indifferent to their desires for a breakwater, and as a result, the men of the community were forced to build it themselves. But to establish a breakwater is no easy task, and the men of Fortune began by hauling layers and layers of brush by horse and wagon and dumping it into the water. Once a layer of brush had been established, it was next followed by rocks which were hauled across Fortune beach, and then by finer clay (1).

With the establishment of a breakwater, the mouth of Fortune River was calmed into a fine and sturdy harbour, one that now offered the potential to support a vibrant lobster industry.

The Johnston’s Lobster Factory

Johnston’s Lobster Cannery, 1948. Photo: Ivan K. Mitchell.

Integral to the success of this lobster industry in Fortune was the operation of the Johnston’s Lobster Factory, which was situated on the north side of the harbour, and was sheltered in part by the breakwater. It was owned and operated by the E.S. Johnston family, who were also prominently known at that time for their corner store which was situated at the southeast side of Fortune bridge (presently the Fortune Bridge House).

Carrying lobsters into the factory to be processed. 1941.

The lobster factory was an ever-expanding compound of several buildings, each with their own purpose. The main cannery building was located right on the shore, and was so close to the water that it was subject to the rising tide and had to be elevated on piers to accommodate shifting sea levels. Twice a day when the tide came in the water would flow right under the building, giving it the appearance that it was floating. It was inside this building that the lobster was actually prepared, treated, and canned. Near that was the cookhouse, where meals were made daily to feed the large number of staff and employees who kept the lobster cannery operating day in and day out. There was also a small pumphouse located on the riverbank below Douglas Aitken’s home, which supplied fresh water to the factory by means of a pipe which ran along the shore.

The Johnstons also owned a house at the wharf where they stayed during the lobster season, and some of their workers, who lived as far away as St. Charles and thus could not make it home every night, boarded with the Johnstons at the harbour during lobster fishing season.

The Cans

But although both a breakwater and lobster cannery was in place, the true miracle which allowed the lobster industry to flourish in Fortune was the development of the technology which permitted lobster meat to be successfully canned and preserved on a large scale. Prior to the large scale accessibility of industrial canning equipment, lobster had posed a uniquely troubling problem which prevented it from being sold on a large scale. Unlike other types of fish, it could not be shipped and preserved merely in salt, due to the nature of its shell and the fragility of its meat. And so, unless one was eating fresh lobster, they would not be eating it at all; a problem which in those days eliminated almost the entirety of the North American population.

However, with the advent of affordable and accessible lobster canning equipment, lobster meat could now be shipped anywhere in the world without spoiling, a development which opened whole new markets for the industry, and which in turn cemented the lobster canneries of the Island into powerhouses of economic production around the first half of the twentieth century.

A Fisherman’s Life

Commercial lobster fishing in Fortune was at that time merely a fledgling industry, and in those early days, “lobsters were first fished in the fall of the year. They fished morning and evening.”

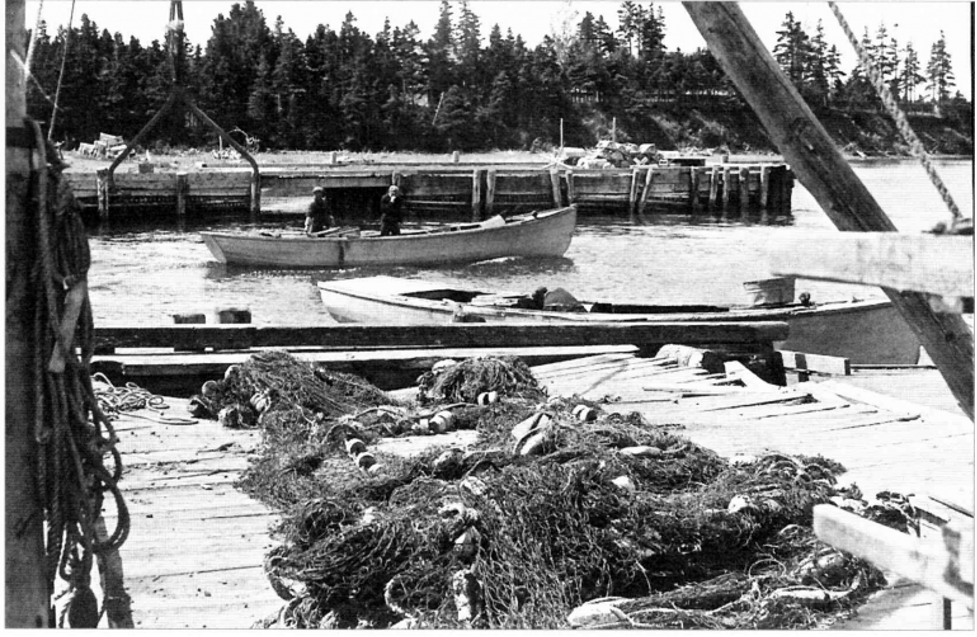

Done for the day. Fortune Harbour, 1941.

This was to allow the men to fish, then to come home and do the farm chores, then go back out again when the work was done for the day. At that time, all lobsters being caught in the area were done so under contract by the Johnston family, where the men, as fishermen, were paid labourers of the Johnstons themselves.

The fall fishery only lasted a short time before the season was moved to the spring time. In those years, they could start fishing as early as April 26th, and it was not uncommon for the men to be required to haul their boats over the ice in order to reach open water. The boats they used were small, one or two men wooden boats which resembled a row boat, and in the earliest of days they were powered by human muscle alone; they were later powered by modified car engines. Unlike today, not all boats were moored at the harbour; some tied their boats up below their own homes on the river, while others who did not live directly on the river opted simply to tie them to the bridge for the night and walk the rest of the way home.

Then, as now, lobsters would be hauled up from the seabed in lobster traps, and then they would be dumped into wooden crates aboard the boat. Back then lobster fishing was constrained to a great degree to inshore fishing, due to the technological limitations of the boats and their trapping supplies and capacity. Notable, also, was the fact that most of these men were unable to swim, being farmers at heart, and deep water posed a real and significant threat to their own lives.

But once the crates on the boats were filled, the men would take their catch back in to the wharf, where the lobster was then weighed and measured, and then transferred to the holding area by the factory, where it would wait to be taken into the cannery.

There, their catch would be cooked and packed in sealed cans, frozen, or occasionally shipped live to many other parts of Canada and the United States, with a great deal of the lobster being caught ultimately destined for Boston.

Working at the Cannery

The lobster fishing season lasted for about two months around May and June. Work in those days was a week long affair. As mentioned above, people traveled from as far off as St. Charles to work in the cannery, and for many it was not possible for them to return home at night. Instead, they would live at the harbour for the duration of the season, going home to visit only on weekends in most cases. Interestingly, many of the workers inside the Island’s lobster canneries at that time were women, for most of the men were preoccupied with fishing and farming obligations of their own.

The Johnstons Cannery, 1933.

Work inside the cannery was centered around preparing the lobsters for the market. Jobs would include “taking the meat out of the claws, tails, arms, and thumbs of the lobster body, using the wringer to press meat out of the legs, washing the lobster meat, making the salt brine to put over the meat in the cans, lining the cans with paper, packing the meat, cleaning the equipment, and washing up the work place” (1).

The men who worked inside the cannery were often employed to do much of the logistical and maintenance work required to keep the cannery itself operational. This included “lifting the crates of live and cooked lobsters, tending the fires and the boilers, cooking the lobsters, operating the can sealing machine, cleaning the lobster claws and arms, disposing of the shells and bodies, cooking the sealed cans in a bath or retort [similar to a pressure cooker, and was used for sterilization purposes], lifting the cases of cans, and using the hose for cleaning the floors and crates and boilers (1).

Building the Boats

All of the fishing boats in Fortune were built by hand, a tradition which continued long past the heyday of lobster canneries, and while all handmade wooden boats have now been retired, their fine workmanship has ensured that some of them survive even to this day.

WORKING ON THE FISHING BOATS BEHIND JOHNSTONS.

Working on the fishing boats behind Johnstons, present day Fortune Bridge House. (Date Unknown).

As a supplement to their own economic industry, Earl Johnston worked with Alfred Higginbotham building fishing boats in his yard during the winter months to help support the Johnston’s lobstering endeavours. The winter afforded an excellent opportunity to have boats built, mended, or repaired for the upcoming spring season, and as such there was little idle time in the calendar to have these boats ready for the water once the ice melted. All of the engines of the boats were removed during the winter months and were stored in a building adjacent to the cannery.

A Changing Industry

In 1940, Lester, the son of E.S. Johnston, took over the cannery, renaming it to “Fortune Bay Cannery”. Lester was a savvy and industrious owner, and under his oversight he expanded his fish and lobster buying influence to include Naufrage, North Lake, Morell and Souris as well.

However, in 1965 the entire operation was sold to Paturels Ltd., and later to National Sea Products Ltd. This change was much in keeping with the changing face of the lobster fishing industry, for it had become increasingly common that canneries were closing as the market for live lobsters had increased with the development of more efficient and viable shipping and transport options.

A further change was the emancipation of lobster fisherman who now worked on their own and chose to sell their catch to the buyer, as opposed to being employed by the buyer at a set wage. This method of independent fisherman is one that continues to this day, and has become the norm on Prince Edward Island.

Today, lobster fishing is still an integral part of the Fortune economy, however all of the once prominent developments which dotted the north side of the harbour have disappeared, as much of the fishing activity has shifted to the south side. Almost two dozen fishermen continue to ply their trade out of Fortune harbour, many of them descendants of those who worked so hard so many years ago to establish the first breakwater which formed the harbour as we know it today. As of 2011, there were 20 boats fishing lobster out of Fortune harbour, each with a crew of several people. There are four lobster buyers here as well: Ocean Choice, Ocean Pride, B.A. Richard, and Mariner Seafood.

References:

Townshend, Bonnie. “The Road to Fortune”. 2012. Print.