The Story of Pearce and Abel

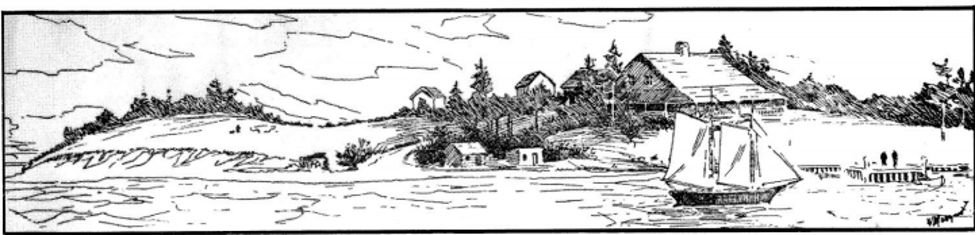

Abel’s Cape, as it appeared in an artist’s sketch from 1901.

The story of Pearce and Abel is one which has long ignited the imagination of Islanders, particularly in the Souris area, for it conjures in the mind a timeless sense of drama and intrigue, of justice and corruption, and of moral ambiguity. It is a true parable and testament to the hardships of life faced by our earliest settlers, and it is a constant reminder of the threat of bureaucratic overreach and what it can do to a man. We as Islanders have always seen ourselves as something of an underdog in the greater scheme of things, and so, most of all, the story of Pearce and Abel resonates with us because it serves as a cautionary tale of what can happen when an innocent man is pushed to his breaking point.

The Land Question

An early map of the Bay Fortune area. Notice that Abel’s Cape is clearly labelled.

When it had last been settled the Prince Edward Island was to remain in control of the British, a problem soon arose as to the settlement and development of the Island. The problem was presented to the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations, who then had the Island surveyed, in great detail, by Samuel Holland.

Upon conclusion of his survey, he divided the Island into sixty-seven lots of 20 000 acres each, which were then distributed, in July of 1767, by means of ballot to those were owed compensation by the Crown for “military or other service” (2).

In exchange for the considerable land grant, the new landowners, known officially as proprietors, were expected to settle their lots with a proportionate population of one person for every 200 acres, and to pay a certain quit-rent to the Crown to provide the settlers with essential community services such as courts, roads, schools, and government administration.

Further, it was stipulated that if the proprietor failed to uphold their end of the agreement, the entire lot in question was to be forfeited back to the Crown (2).

Settling Lot 43

A painting of the HMS Aeolus, which carried Patrick Pearce to Bay Fortune.

Whether through fate or fortune, ownership of Lot 43 eventually fell upon Lord James Townshend, who entrusted one Edward Abel (also spelled Abell) “a farmer and merchant” to act as his agent (O’Grady). Abel was well-to-do by the standards of his day (2), however he was not a popular man among the people of the area. Captain Frederick Marryat, an English sailor and novelist who met Abel on the Island in 1811, wrote in his book, Frank Mildmay, or the Naval Officer: “This fellow called himself the steward, and from all I could see of him during our three week’s stay, he appeared to be rascal enough for the stewardship of any nobleman’s estate in England.”

Other contemporary reports of Abel all echo the same sentiment, namely that he was “officious and obnoxious in his dealings with tenants, and, it is said, “applied for so many summonses and foreclosures against the tenants in distress that he sometimes found it difficult to get a Justice of the Peace to act for him” (3). Both Nicholas Falla and John McKie, whose names appear in early Bay Fortune Church records, refused to act for Abel, Falla saying on one occasion, “It is unpleasant business” (2).

This opinion is echoed by the late Harry Burke of Fortune, in a taped conversation recorded years ago: “I guess he was a good enough man for the people he was working for, but he was a cruel son-of-a-gun.” (2).

Despite his parsimonious behavior with the tenants, Abel lived in relative prosperity; he lived in a cottage on the Cape, which was in Lot 43, and also owned a 500 acre property at Red House (3) which he used as a sort of country residence (2).

By all accounts it seems that Abel’s wife, Susannah Hubbard, was cut much from the same cloth. She was described as being “a selfish and unscrupulous woman who goaded him on to acts of harshness and injustice” (3), and the Supreme Court records tell of one trial (Mary Blake versus Susannah Abel) during the course of which she was forced to deny that she had “scratched Mary’s face or neck or used any violence” (2).

Enter Patrick Pearce

There is dispute as to the precise origin of one Patrick Pearce (also spelled Pierce). According to O’Grady, Patrick Pearce was born in 1789 in Ireland, and it is believed that he immigrated to the Island in at 1811 after the near wreck of the frigate, the Aeolus at the age of 22 (2,3). It is recorded that he had previous military experience, and that he was eager to settle in this new place, and to stake out a life for himself. In any case, it is known that he, like many other settlers in the area at that time, had established and developed homesteads in the area surrounding Fortune Harbour, near Abel’s Cape, however it should be noted that the cape was not called that name at the time.

An early nineteenth century property map of Lot 43, showing the properties of both Pearce and Abel.

In exchange for the use and cultivation of the land, it was expected of tenants that they pay quitrents to Lord Townshend, at “a yearly rental of one shilling sterling per acre or five pounds, eleven shillings and two pence Island currency per 100 acres equal to about three pounds fourteen shillings British sterling” (1), which is approximately equal in today’s terms to somewhere between $150-$200 per acre.

Pearce was a tenant of 100 acres, and he occupied the home nearest to Fortune Harbour (1). J.C. Underhay recalls seeing “some of the logs of his house forming part of a fence about seventy years ago.” Counting backwards from his time of writing, that would have been just prior to the 1850s.

This information conflicts however with Townshend’s report where she indicates that “Patrick Pearce chose one hundred acres in the Red House area, the land now owned by Mrs. Majorie Stead.” In the absence of any other evidence, one is taken to lend credibility to Townshend’s account, as she has included the map, seen here, which clearly indicates Pearce’s property. In Underhay’s defense, however, it is more than entirely plausible that he too had the right location, and that our present-day understanding of his directions is at fault for the misunderstanding.

In any case, by the summer of 1819 Pearce had been living in his home for some twelve or fifteen years, and he evidently farmed reasonably well, as there is no indication that he ever had any prior conflicts with the law, nor was he evicted. And as some measure of his farming success, it was around this time that he came to be in possession of a beautiful black horse, one which soon came to be known as the finest horse around (1).

For the Love of a Horse

This did not sit well with jealous Mrs. Abel, who looked on with a covetous eye, “and tried in vain to induce Pearce to sell him” (1). Pearce was not to be persuaded, and so, “failing in that, she prevailed upon her husband to demand immediate payment of the rent.” Despite the fact that Pearce was not owing on any rent at that precise time, Mrs. Abel was certain was that if she could force him to be owing, he could be persuaded to surrender the horse in exchange for the debt he owed. But poor Pearce was not to be trifled with so easily, and somehow, through the support of his neighbours, Pearce succeeded in getting together that which the Abel’s demanded (1). This did little to satisfy Abel, however, who then claimed that the money he had collected was local currency, and thus of no use in England. This was merely a technicality, but it left Pearce scrambling to procure the amount owed, in a time when British currency was a scarcity among the community (1).

A restored Queen Anne’s Musket; the exact style that Pearce would have used against Abel.

Pearce did find the money, but when he returned home he found that Abel was already sitting on his woodpile waiting for him, with Constable John O’Donnell beside him, holding the coveted horse by the bridle. Pearce offered Abel the money, but to Abel the outcome was already a foregone conclusion: he was there to seize the horse. This incensed Pearce, and what happened next was recorded at the time in the Prince Edward Island Register of 8 September 1819:

“Abell… sent his bailiff to some person living in the settlement to witness his proceedings; and the bailiff, upon his return, heard a loud altercation between Abell and Pearce, and saw the latter enter his house and take down a musket and fixed bayonet which he placed upon the floor, and then taking off his jacket, took up his gun and proceeded to the spot where Abell was seated and made a lunge which pierced Abell’s arm, and immediately making a second charge the bayonet passed through the back part of the thigh into the intestines. He was then seized by the bailiff, who wrested the gun from him and held him fast, while Abell crawled to the house. The bailiff (who is also a servant to Abell) was sent for to attend his master and Pearce absconded” (2).

Despite his injuries, “Abel managed to crawl to the next house, occupied by Valentine Needham, another of the emigrants, from whence he was taken to his own house. Abel made his will on August 26, 1819, two days after he was stabbed. He left to his “dear beloved wife” all “houses, land, stock in trade, stocks, livestock, farming utensils, books, bonds, vessel, household goods, ready money, debts, jewellery, plate, and wearing apparel…. ” He died two days later, on September 7, 1819 where he died after lingering for a week” (1,2)

Pearce’s Escape

Meanwhile, Patrick Pearce became a fugitive, taking shelter among his fellow tenants, many of whom sympathized with him. His neighbours were putting themselves at great risk by harbouring Pearce, but for them it was well worth while. The memories of persecution in Ireland at the hands of the elite ruling class were still all too fresh, and many no doubt remembered “the penal times in Ireland, when possession of a fine horse was considered to be the exclusive prerogative of “fine Ascendancy gentlemen,” and Catholic “bogtrotters” could therefore be dispossessed of any horse valued at over five pounds.” (3)

An early insignia, created by some of the residents of Abel’s Cape.

Not only did Pearce’s neighbours put themselves at risk for harbouring a fugitive, they did so while ignoring a considerable reward of £20 which had been offered for his capture. A notice which appeared in The Prince Edward Island Royal Gazette of 2 February 1820 stated that “for the apprehension of the said PATRICK PIERCE [sic], and lodging him in the Goal of Charlotte-Town, the said Reward to [be] paid on conviction of the Offender. And all His Majesty’s Justices of the Peace, Constables, and other Persons are enjoined to use their utmost vigilance in apprehending the said PATRICK PIERCE. And all Masters of Vessels and other Persons leaving this Island are warned to be particularly careful to keep a watchful eye that the said PIERCE is not suffered to make his escape on board of any Boat or Vessel” (2).

The £20 sterling reward was a large amount of money in the Island colony in 1819. It would have paid a tenant’s rent for four years, but to betray one of their own and side with the landlord and his oppressive agent would have branded a man a traitor (2). According to O’Grady, “Pearce’s friends, regardless of their national or sectarian background, probably realized that in sheltering him in their woods and cellars, they were re-enacting a long-standing Irish practice of harbouring fugitives from abusive authority. And while the legal and moral implications remain subject to debate, it seemed only right that “the ordinary people of that time did what they thought necessary to assist their neighbour in distress.” (3)

The precise machinations of his escape are unknown, for as O’Grady explain, “one hundred and eighty-five years after the event it is not possible to establish all the details, but a composite version of traditional accounts indicates that Pearce managed to hide in the woods or with sympathetic friends during the winter of 1819.

First, a family named Burke sheltered him in their cellar, then Joseph Brown and John Black took turns concealing him at Cape Spry. In the spring of 1820, Pearce “swam across Blackett’s Creek and stayed the night in the attic of George Banks’ home in Annandale. The next day the young Banks girls, Mary and Elizabeth, dressed the fugitive in their mother’s clothes and rowed him out to a vessel anchored in Grand River” (2). From there, an American sea captain, Nicholas Falla, transported him to safety. After that, Pearce simply disappeared. As Harry Burke said, “No one ever heard of him after.” (2)

Legacy

In living surnames Pearce and Abel have long faded, but in recorded memory these characters have left an indelible mark upon the communities that they once called home. The name Red House still remains, and for a time Abel’s Corner Gas & Convenience bore testament to the familiar name. Now, however, it is only Abel’s Cape, situated between Fortune Harbour and Fortune Back Beach, which bears the name as a permanent reminder of the way things once were here on the Island.

So too does the story of Pearce and Abel live on in the writings of Adele Townshend, in the form of a play, entitled For the Love of a Horse. As a dramatization of the events of the story of Pearce and Abel, For the Love of a Horse won an award in the Ottawa Little Theatre Annual Playwriting Competition, and received ” a glowing review by Dora Mavor Moore in the 1968 Canadian Playwriting competition.” The play was later performed in Lethbridge, Alberta, as part of the City Drama Festival, and went on to receive a full scale production by TheatrePEI in 1986.

References:

MacKinnon, D.A. “Past and Present of Prince Edward Island”. B.F. Bowen and Co., Charlottetown, PE. 1906. Print.

Townshend, Adele. “Drama at Abel’s Cape”. The Island Magazine. 1979. Print.

O’Grady, Brendan. “Exiles and Islanders: The Irish Settlers of Prince Edward Island”. McGill-Queen’s University Press. 2013. Print.